- Home

- Florencia Clifford

Tales From a Zen Kitchen

Tales From a Zen Kitchen Read online

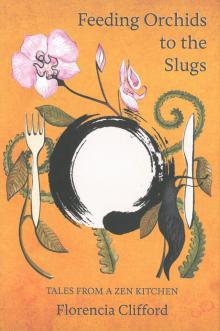

Feeding Orchids to the Slugs

Tales from a Zen Kitchen

Florencia Clifford

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

How to use this book

This is a book about the journey of learning to be a Zen cook. It is about cooking, and the stories that arise when you are cooking. It is about the healing that occurs when you can look at your problems face to face and make friends with your ghosts. Although I cook mainly at the Maenllwyd, I also cook for Buddhist retreats in other parts of the country, and I cater for the teacher-training courses in my local Steiner School.

Whilst I have included recipes, my style of cooking is instinctual. It is about connection and experiment. I do not plan menus. I am inspired to create meals by ingredients in season: meals emerge out of the mood of the retreat. Each day is fully creative, and slowly the dormant artist in me, my hidden, wilder self, has emerged through my cooking.

Please use the recipes as a guideline. Although they have been tested, there is always room in a recipe to make it yours. Chop the vegetables in the shape you’d like them to be, think of colours and presentation. Get to know your ingredients: from the moment you source them, to the preparation, to the cooking, to the offering, to the eating.

And before you start, learn to really taste your food, as this will help in your cooking. Try this exercise in meditative eating with a handful of mixed fruit and nuts. Pour the contents into the palm of your hand, and place one of them at a time in your mouth. Close your eyes, feel the shape as your fingers pick it up. Notice the texture in your palate, don’t think about anything, feel it as you chew it, notice where the flavours move inside your mouth, how it feels like when you swallow, what it tastes like. Take your time, don’t rush it. Are they similar in taste? Pay attention to what happens when the dried fruit begins to hydrate in your mouth. Do you know what you are eating? Where has it originated from? Think of the person who harvested it, packed it, then return to the taste. Once you have practised with fruit and nuts, try it out with a meal.

Florencia Clifford

Foreword

In the early part of the 13th century C.E., a young Japanese Buddhist monk, disenchanted with the stagnation of the teaching in his native land, left on a long and perilous journey to China to find a teacher who could guide him to enlightenment. On his way, he met an old monk, the Chief Cook from A-Yu-Wang Mountain monastery, who through example and simple instruction was to have a profound effect on the young seeker’s awakening. The traveller’s name was Eihei Dogen, and he was to become the founder of the Soto Zen school of Japan, and one of the most influential teachers in the history of Zen. One of his seminal written works is entitled Instructions to the Cook (Tenzo Kyokun) and to this day, the cook is considered the most important and respected person in a Zen monastery. Why? In describing one woman’s path to becoming such a cook, this lovely, honest, revealing book goes some way to providing an answer.

I first met Flo in the kitchen of a retreat centre on the edge of Dartmoor. I was acting as Guestmaster for a retreat being led by Jisu Sunim, a Korean Zen master, and she, of course, was acting as cook. Although we had both been connected for many years with retreats at the Maenllwyd, a remote retreat centre in the wild hills of mid-Wales, our paths had for some reason never crossed before. I was impressed by how she was able to immediately inhabit this new space, and quietly, efficiently and mindfully organise it for the coming week. A Zen retreat cook’s life is not easy. The schedule begins with rising at 5 am, and ends with bedtime at 10 pm. During this time, the cook needs to produce breakfast, lunch and evening meals. Although she has help from assistants drawn from the participants (work periods are an important part of retreat practice), it is the cook’s responsibility to ensure that all the food is ready at the appointed time, that there is a sufficient amount (but no excess), and that any participants with specific dietary requirements are catered for. She must organise the preparation, serving and cleaning up of the meals and the cleanliness of the kitchen. She is also expected to participate in as much of the retreat schedule as her workload allows.

This then is the external activity of the Zen cook. But there is far more to her contribution than this. The Master’s work is of course to guide and offer teaching, to care for the spiritual life of the retreat. The Guestmaster’s job is to oversee the smooth running of the centre, to organise the complexities of a group of people living in close and silent proximity, to manage the temporal aspects of the event. One might say that the cook’s role is to bind these worlds together, for of course the temporal and the spiritual are not in fact separate and are seldom more intimate than when we mindfully partake of food. In many ways, the Zen cook could be seen as a manifestation of Kwan Yin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, She Who Hears the Cries of the World. A Zen retreat is no holiday: it is often a time of deep self-encounter, and this may lead to the surfacing and release of much suffering as well as joy. Flo’s kitchen becomes a place of refuge, where a cup of tea, a piece of home-made cake, or even just the warm glow of a Rayburn and the wonderful aromas of slowly cooking food can bring a return to peace, balance and gentle determination.

Flo has a knack of knowing what is needed, and of quietly, unobtrusively and appropriately providing it. Her cooking reflects the spirit of mindfulness and compassion that is at the heart of Zen: her dishes are not only deeply nourishing to the body, but renewing to the spirit. They are beautiful to look at, not from ostentation but from a recognition that in presenting food beautifully we are honouring all the beings who have made the presence of this meal possible, and the deep and unbreakable interconnectedness of all existence. Her choice of ingredients and how they are combined are skilfully connected to the current “mood” of the retreat: Flo’s menus are responsive, not set. And like all good Zen cooks, Flo recognises that her work in the kitchen reflects her work with her self. Cooking is not a task, or a job, but a practice. This takes real courage for, whilst the practice of the retreatants sitting on their cushions is invisible to others, the cook’s practice is revealed to all with every meal she serves.

So please, savour this book as you would a Zen meal: putting aside expectations, classifications and comparisons, taste each morsel, see how it resonates with your own practice, your own experience, your own work. And although there are many delicious recipes tucked inside these pages, the main one is this: in responding to each moment with authenticity, inquiry, compassion and mindfulness, we truly encounter the wonder of our lives.

Ned Reiter (Guo Ji), Registered Medical Herbalist Somerset, July 2012

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1A Welsh Farmhouse

Chapter 2Retreat 1: The Little Girl

Chapter 3Storms and Siestas

Chapter 4Retreat 2: Learning the Ropes

Chapter 5Tara

Chapter 6Retreat 3: Dancing with Death

Chapter 7La Granja

Chapter 8Retreat 4: The Art of Cooking

Chapter 9Porridge

Chapter 10Retreat 5: Cooking in a New Kitchen

Chapter 11Fina

Chapter 12Retreat 6: The Pilgrim Cook

Chapter 13Pomegranates

Chapter 14Retreat 7: Death of a Teacher

Chapter 15Ongamira

Chapter 16Retreat 8: Countless Jewels

Chapter 17Butterfly

Chapter 18Retreat 9: Transformation

Chapter 19Fly

Elements of the Zen Kitchen

Prologue

Love makes you see a place differently, just as you hold differently an object that belongs to someone you love. If you know one landscape well, you will look at all other landscapes differently

. And if you learn to love one place, sometimes you can also learn to love another.

~ Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces

I was born and grew up in Córdoba, a mountainous region right in the middle of Argentina, splashed with blue hills that stretch west towards the Andes. For the first half of my life, I was embraced by slopes of rock and grasses, pink peppercorn trees, open skies and the Southern Cross.

For the past two decades, living in York, away from my native landscape, it is the mountains I have missed the most. I have recurring dreams in which I open my kitchen window and I see the outline of the cerulean hills undulating on the horizon. Places shape your life and sway you in a lasting way; they imprint you.

Although I grew up in Argentina, I always felt a strong sense of familiarity with Britain. My paternal ancestry is Scottish, but even though we never interacted with the ex-pat community, remnants of my grandparents’ heritage and culture tinted our lives in different ways. I clearly remember the feeling of melancholia, of homesickness, that came to me in waves, when I thought of Britain. As a child I longed for the wilderness of Scotland. I proudly showed my friends the family tartan and listened to The Beatles and Highland music on vinyl. We dreamt of riding double-decker buses in London, of hearing Big Ben, of walking around the foggy streets, even though I remember Grandpa saying that London smelled of sprouts.

My sister Magda and I made up Scottish dances in the living room. In the summer, we spent part of our holidays in El Reposo in Ongamira, a remote place in the mountains where Grandpa took us because it reminded him of Scotland. He had never lived in Scotland, it had never been his home, yet he felt nostalgic about it, and so did we. A yearning embedded in the family’s way of being flooded our silences.

At school, my sisters and I were considered Inglesitas (little English girls) during the Falklands War, and some of our classmates treated us like the enemy. The extended Clifford family gatherings were carried out partially in English: we drank leaf tea in china cups and ate scones with jam, drop scones with savoury toppings, cucumber sandwiches and fruitcake.

Some of our relatives even had a portrait of the Queen in their living room. The fascination with all things British meant that their houses were full of tea caddies, cake tins, thimbles, tea towels and naff souvenirs with pictures of the latest royal wedding. There was a sense of nostalgic pride and celebration. After a visit by my great uncle and aunt to London in 1981, we were showered with Charles and Di engagement souvenirs: a jigsaw puzzle (on which I can vividly remember the bluebird print of Diana’s shirt) and two celebratory mugs, which we kept in the kitchen as kitsch ornaments. The presence of the mugs aroused suspicion amongst our neighbours when the war broke out, and one knocked on our door to find out what we intended to do with them. Dad suggested we built a big bonfire in the street, in which we would burn the mugs, publicly displaying our loyalties. He was being ironic, but in truth, we did not support either side. We used to listen to the BBC World Service on our short wave radio, so we could get the other side of the story.

Whenever I look back at my ancestors, I see people leaving their homes in Europe to make a new life, to inhabit the new world. Buenos Aires had opened its doors to the world towards the end of the nineteenth century with a candid and alluring invitation to a sanctuary, to a land that was rich and wild, in need of population. People flocked in ships from all over Europe, from Syria, from Lebanon, from Armenia. Eastern European Jews escaping pogroms; Italian peasants looking for their only chance of owning the land they farmed; Welsh émigrés attempting to maintain their Welsh ways, settling in Patagonia; the French; the Basques. The British invested more money in Argentina at the start of the 20th century than they did in India Argentina is a melting pot where people mingled and settled and worked hard to build a nation, but the collective unconscious was, at the time when I was growing up, soaked up with melancholic cries for home.

My own experience as an émigré led me to identify with my grandmother, Mary. She met my grandfather, Alec, on a train journey from London to Glasgow. Mary was being harassed by a drunk and Alec, who was visiting his father’s home town, interfered. They started chatting, realised they were going to the same place, and soon began courting. Alec returned to Argentina and after exchanging letters for a few months, she agreed to marry him. On her own, she made the long voyage by ship to Buenos Aires. They married in the docks, as soon as she landed, as a law had just been passed to prevent single, unaccompanied women from entering the country. At the time many immigrant women were being tricked into prostitution.

Thirteen years and three children later, she managed to return to Scotland, for a visit that lasted two years. My dad was only a small baby. She only ever made two trips home to see her family again. They never managed to visit her. She died when I was six, a frail, gentle lady who hardly spoke when we were around; my memories of her have faded.

I can see myself, holding on to the doorframe of her bedroom in the house next door to ours. I see her, a tiny woman in pristine white bed-clothes, bedridden. Her bedroom had a French, triple-door, rococo armoire with a mirror, which momentarily held both our reflections: a little girl tiptoeing quietly, like an outsider, watching from a distance, attempting to connect to the woman with the long silver hair lying on a bed, staring out of the window. I vividly remember this room, which smelt of medicine and flowers. She died in that room and we were whisked away in the middle of the night to stay with my other grandmother in the country. I think I must have been taken whilst I was asleep, because I remember waking up in a different bedroom and hearing the grown-ups whispering to each other. The words were almost lost in the hush of the early dawn and in the rustle of people coming in and out, but I knew she was gone. We were told properly later that day and we did not attend the funeral. She suffered from heart disease and my dad tells me that the symptoms were made worse by her depression and homesickness: the longing for home got hold of her and took her while she was still relatively young.

We were obsessed with British ingredients. We adored Cadbury’s chocolate, Twining’s tea, Coleman’s mustard powder mixed with water in a little silver and blue glass dish which accompanied our roast beef. On Sunday nights we used to have a few drops of Lea & Perrin’s Worcester sauce in our simple broth with handfuls of tiny pasta shapes, to compensate for an undoubtedly enormous lunch in the country at my maternal grandparents’ house. We also liked a splash of Lea & Perrin’s on crispy fried eggs. There was a time when my parents were hard up and we ate a lot of eggs.

Our interest wasn’t confined to British food – we loved the foods of the empire. We sprinkled curry powder on white rice, and my dad would buy exotic spices from a shop in Buenos Aires called El Gato Negro. He used to go to Buenos Aires to work a lot when we were kids, and on one of his trips he discovered the shop so he brought back the brochure. It contained long lists of tea blends, a wide selection of coffee beans from around the world, and spices. The brochure was black, red and white with a picture of a black cat, Belle Époque-ish, which spoke more of the Moulin Rouge than of an exotic spice shop. My mum, thinking my dad had been to a cabaret, threw the brochure back at him and stormed off. I still grin when I think of that brochure, and I have visited the shop in Calle Corrientes a few times: a fascinating, turn of the 20th century store, with oak counters and ash shelves, bronze chandeliers and Thonet chairs. The smells are captivating, the spices impregnate the air, and the coffee beans are roasted in the original machine. You can sample the blend of your choice in a perfect espresso. It has now been named a historic heritage site.

Although there is no legacy of recipes that have been passed down from the Scottish side of the family, apart from poached egg on toast, and drop scones which we ate with the Argentinian staple, dulce de leche, I think that my curious and adventurous palate came from that innate curiosity for new flavours that most British people have. We were, in a culinary sense, a lot more adventurous than most people we knew. And yet, amongst all the exotic favourites, there were f

lavours and predilections that I found hard to fathom: my grandfather’s love for Bovril on toast, for spam, for tinned corn beef sandwiches. In a country where you could eat fillet steak every day, these British war-time substitutes for “real” meat were unnecessary, yet I imagine he chose them because he relished the connection, they fed his melancholia. Food can do that; it can bring you that warmth of home in one evocative mouthful. So I see him, my Grandpa Alec, my gentle giant, sitting alone in his kitchen, with a cup of tea and a book by his side, eating his English food, thinking of his parents, of his wife, of his dead daughter, Betty, of the Fairlie Moors. The constant longing of the émigré lived in him and in all of us. The loves were lost, yet returned, momentarily, in each bite.

He encouraged me to read and as a child I devoured books; we had an impressive library. I read Penguin Classics and Ladybird children’s picture books. Shopping with Mother was my first glimpse into British shops, bakeries and iced buns, meat wrapped in waxed paper, sweet shops. Those books were like small windows into British suburban life, traditions, wildlife. Later I began to take books from the big bookshelves: Wilde, the Brontës, Dickens, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, all books that fed my imagination, connecting me with the culture and landscape of the British Isles.

As I became a teenager, the longing and fascination shifted towards music. It was the mid 1980s. The military dictatorship, or junta, had ended and suddenly there was a new wave of music, from both Argentina and abroad. It was freely available although sometimes difficult to get hold of. I travelled to English cities in my head through music, from my bedroom, through a cassette player and the first FM radio stations. I slept with music, woke up with music and found an indie-pirate record store that managed to get rare imports from the UK. They made compilation tapes of my favourite songs or I recorded over my dad’s TDKs from shows on pirate radio stations. Perhaps it is true, as a friend of mine says, that despite not being a colony, we too were victims of the empire. The hidden empire imposed a language that wasn’t ours, and music that didn’t belong to our experience. But I was happily colonised by David Bowie and Peter Gabriel, by The Cure, by Japan, by Joy Division. This was music that meant something to me, that resonated with my inner angst, with my being.

Tales From a Zen Kitchen

Tales From a Zen Kitchen